Please click here to access the main AHDB website and other sectors.

- Home

- Knowledge library

- Pepper fruit rots: disease recognition and biology

Pepper fruit rots: disease recognition and biology

Learn to spot the signs and symptoms that appear on peppers when they are infected by one of the more common fruit rots.

This information was last updated in 2015.

Bacterial soft rot

There are several bacterial species responsible for these rots on peppers.

Most commonly, they are:

- Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. carotovorum

- Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. atroseptica (previously Erwinia carotovora pv. carotovora)

- Erwinia carotovora pv. Atrospetica

- Dickeya chrysanthemi.

Also listed as pathogens of pepper fruit, though not in the UK:

- Bacillus polymyxa

- Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria

- Cytophaga sp.

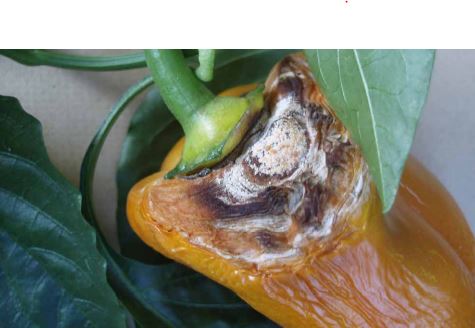

Figure 1. Bacterial soft spot. © Tim O’Neill.

How it spreads

These bacteria are spread from soil and plant debris by wind, water, insects, and people.

Infection can spread from one infected fruit to adjacent healthy fruit, resulting in high losses post-harvest.

Once the crop is harvested and packaged, condensation can increase the likelihood of bacterial rotting. Post-harvest rotting begins around wounds, or at the stem end near the fruit stalk.

Weather

Infection occurs at wounds when conditions are warm and wet, especially above 20°C.

An outbreak of bacterial soft rot in the Netherlands was associated with prolonged poor weather in summer.

Peppers vs other crops

On peppers, bacterial soft rots caused by Pectobacterium initially cause slightly depressed lesions with water-soaked margins.

Degradation of tissue occurs quickly, and infective juices may leak when the skin splits.

In tomatoes and some other crops, soft rots are associated with a characteristic bad smell. This does not occur in peppers.

Botrytis fruit rot

Lesions can appear anywhere on the fruit, and infected tissue is water-soaked and light brown.

Commonly, the epidermis can be peeled away easily from infected tissue.

In high humidity spore production occurs, which appears brownish-grey and fluffy (see figure 2). Spores are readily spread by wind.

Sporulation most often occurs at the centre of the lesion where the epidermis has split, or on the calyx (see figure 3). Sclerotia are black, hard aggregations of fungal mycelium measuring 4-11 mm that may form as the rot progresses.

Figure 2. Botrytis infection on fruit showing grey sporulation and associated water soaked tissue. © Tim O’Neill.

Figure 3. Botrytis on fruit stem can often spread into fruit issue. © Tim O’Neill.

Soil, flowers, and fruit

Botrytis sclerotia can persist in soil or in crop debris, and spores produced by them are spread around the glasshouse by air currents.

Senescing flowers which remain on the plant are also susceptible to Botrytis infection. Petals which fail to detach from set fruit may facilitate fruit infection.

Fruit infection is most common during overcast, cool, and humid conditions and where planting density is high.

Fusarium fruit rot (external)

Lesions appear water-soaked and sunken, but remain firm, and white. Pinkish or yellowish mycelial growth can often be seen (see figure 4).

The boundaries of fruit lesions are well-defined and infected flesh becomes pale brown.

Figure 4. A mature fruit showinign an external Fusariam fruit rot while still on the plant. © Tim O’Neill.

Figure 5. Fusarium solani can cause stem lesions that can lead to wilting in the whole plant.

of the sexual stage of Fusarium solani associated with pepper stem base rot - Tim O'Neill.JPG)

Figure 6. Orange-coloured fruiting structures (perithecia) of the sexual stage of Fusarium solani associated with pepper stem base rot. © Tim O’Neill.

Dispersal

These fungi are dispersed by wind and in water. Generally, infection only occurs if fruits have been weakened or damaged.

Fruit contaminated with spores at harvest may be susceptible to post-harvest rotting if stored incorrectly, at too low temperatures or in high humidity.

Different species

External Fusarium fruit rot may be due to several species of Fusarium, including

- F. solani, F. oxysporum, F. equiseti and lactis.

- Fusarium solani is the main cause of external fruit rot in the UK.

- With F. solani, the orange-coloured, sexual spore stage (Nectria haematococca) is quite common.

Fusarium fruit rot (internal)

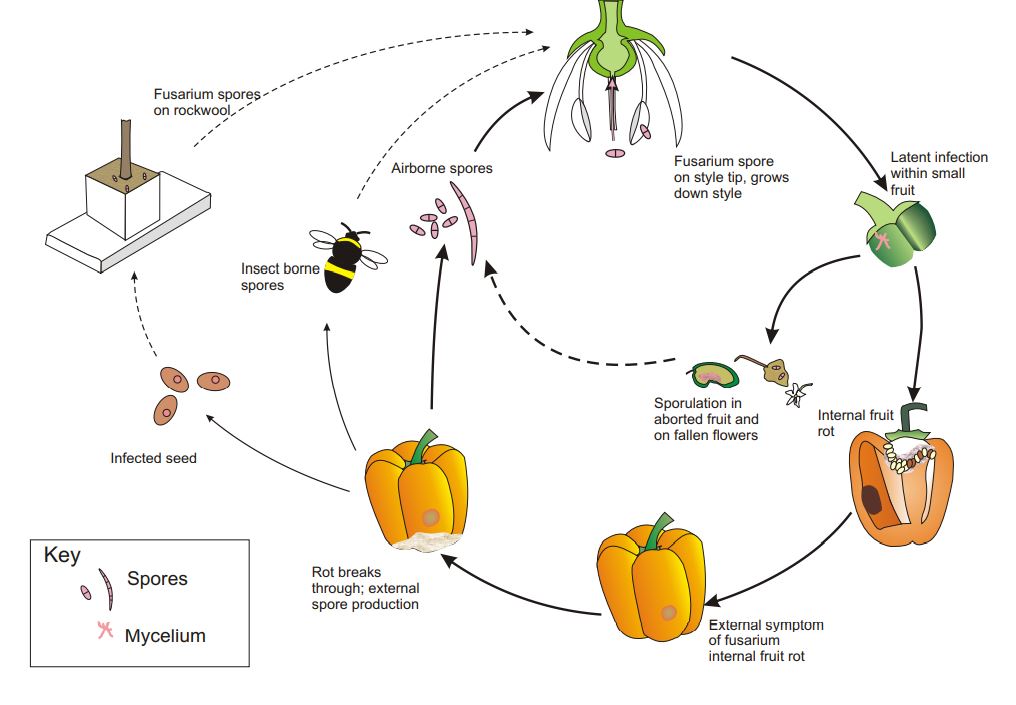

Fusarium internal fruit rot is primarily due to F. lactis. It infects at flowering and grows down the flower’s style to cause an internal rot in developing fruit on the plant.

The fungus may remain latent in infected fruit and only appear at harvest, or once it is with the retailer or been sold to the consumer.

This fungus, as with other Fusarium species, may also be spread by wind and water.

It has recently been found to grow and sporulate on the surface of Rockwool slabs in glasshouse.

Figure 7. Cross-section of a pepper fruit showing symptoms Fusarium internal fruit rot. © Tim O’Neill.

Figure 8. First sign of Fusarium internal fruit rot is a small, brown water-soaked lesion. © Tim O’Neill.

Figure 9. Fusarium mycelium growing over the seeds inside infected fruit. © Tim O’Neill.

The symptoms

Internally, peppers exhibit a pale brown rot, often with white/peach-coloured mycelium which may also infect and grow over the seeds (see figure 9).

Externally, the rot is often invisible, but may start to show as a small, depressed, browning lesion (see figure 8).

Figure 10. Proposed life cycle of Fusarium lactis cause of fusarium internal fruit rot of sweet pepper. As well as occurring in flowers, young fruit and mature fruit, F. lactis has been found to occur naturally on ungerminated pepper seed, on wild bees in glasshouse and on the surface of rockwool cubes in pepper crops. Solid lines indicate known stages in the life cycle; dotted lines indiciate unproven stages.

Mucor/Rhizopus

Mucor moulds are white with black spore heads (figure 11) and cause a soft wet rot where the skin remains intact.

Rhizopus rot appears similar and is primarily caused by R. stolonifer.

Lesions are soft and water-soaked, but not discoloured. The skin may rupture and leak the broken-down fruit, with an odour of fermentation.

Figure 11. Distinctive black spore heads are indicative of Mucor infected fruit. © Tim O’Neill.

Where is the mould found

These fungi commonly exist in the air and soil in an asexual form and germinate in warm (around 25°C) and moist conditions.

Peppers are only infected at wound sites or in growth cracks.

Mucor and Rhizopus rots are more common post-harvest than pre-harvest, especially following rough handling.

Fruits may be engulfed quickly by Mucor and Rhizopus rots, which can spread in crates from affected fruit to those in contact with it.

Phytophthora capsici

Fruit rot caused by the oomycete P. capsici generally starts at the stem-end of fruit as mycelia have grown through the peduncle.

Infected tissue is initially water-soaked and takes on a dark green colour.

Humid

In humid conditions, mycelium and sporangia can develop on the fruit which are off-white in colour and can further spread the disease.

Infected fruit rapidly dries and shrivels but does not drop from the plant.

Sporangia release zoospores, which can infect uninjured tissue if splashed onto the aerial parts of the plant. They are also motile in water.

Optimum conditions

Optimum conditions are 24-33°C with free water present.

Fruit in contact with the ground is more likely to become infected.

The disease can be seed-borne and can survive in soil for long periods as resting spores.

Healthy

This rot can also appear post-harvest and spread into healthy fruit.

Phytophthora capsici may also result in loss of plants, as the roots, stems and foliage are also susceptible to infection.

This disease is not established in the UK and any suspected outbreak should be reported to your local Plant Health representative/office.