Please click here to access the main AHDB website and other sectors.

- Home

- Knowledge library

- Identification and control of bacterial blotch on mushrooms

Identification and control of bacterial blotch on mushrooms

Find out about the methods of detection used to identify the presence of bacterial blotch and how different pathogenic species of Pseudomonas are identified. Also read about potential control methods for this challenging disease.

Go back to the bacterial blotch main page

The challenges of identification

Generally, isolations are done from mushrooms with blotch symptoms in a laboratory and each bacterial isolate is then tested using several methods. These methods can include molecular tests and pathogenicity tests, which are used to determine if the known Pseudomonas strains are the possible cause of symptoms.

The key challenge in detecting blotch causing Pseudomonads is developing tests that are specific to pathogenic strains without causing cross sensitivity to harmless or beneficial strains. These tests also need to be sufficiently sensitive to detect pathogen inoculum in mushroom substrates, growing rooms and machinery.

Molecular tests using quantitative real time (TaqMan) polymerase chain reaction can detect and identify most isolates of P. tolaasii, ‘P. gingeri’ and P. costantinii. These are the strains that cause severe blotch in the UK and these tests allows their identification without cross reactions with other non-pathogenic Pseudomonas strains.

P.tolaasii has been detected in peat, lime, fresh casing material and compost. However, the inoculum is usually below the detection threshold for the above tests, and it is not until substrates are colonised with mushroom mycelium, which stimulates a large increase in the Pseudomonads population, that it becomes detectable. Incubation of a substrate sample, such as casing material, in a solution containing an 8-carbon compound (which acts as a selective nutrient source for Pseudomonads) can boost the inoculum in a sample to above a detectable concentration. In the event of a blotch outbreak, it may be possible to detect the pathogen source using this pre-enrichment technique.

Controlling bacterial blotch

Managing humidity and airflow

The conditions which encourage blotch are associated with moisture, such as the persistence of water on caps for more than three hours. Reduce this risk by avoiding watering developing mushrooms and maintaining a sufficient airflow across the beds.

It is important to try and prevent dew point conditions on the caps. Dew point is encouraged by a high humidity and fluctuating air temperature.

Where blotch is prevalent:

- the relative humidity should be kept at 85%

- air temperature fluctuations should be less than 1°C

- an airflow of 1 - 2 m/s should be maintained uniformly across the beds.

How does the Pseudomonas causing the bacterial blotch affect its control?

There is circumstantial evidence from mushroom farms that the epidemiology of blotch may differ according to the causative Pseudomonad pathogen.

Brown blotch (P. tolaassi)

Given conducive conditions (sufficient cap moisture) nearly all mushroom crops will be affected by brown blotch caused by P. tolaasii so it can be assumed that this pathogen is (almost) ubiquitous in the raw materials (Figure 9). Control of watering and environmental conditions are therefore most important for control of brown blotch. However, since the concentration of the pathogen increases rapidly in the casing during a crop, disinfection and cooking-out of growing rooms may reduce disease severity in subsequent crops.

Joana Vicente

Joana Vicente

Figure 9: Mushroom substrate at a farm, where P. tolaassi can likely be found

Joana Vicente

Joana Vicente

Figure 10: Mushrooms ready for harvest

Ginger blotch (P. gingeri'/P. fluorescens) and P. constantinii

Ginger blotch caused by ‘P. gingeri’ has been associated with outbreaks on several mushrooms farms at the same time due to contamination of batches of casing material.

Speckling and pitting caused by P. costantinii has been associated with individual farms, with other farms receiving the same casing materials not observing disease symptoms.

Although blotch caused by ‘P. gingeri’ and P. costantinii can appear under ‘normal’ environmental conditions which would not normally trigger a brown blotch problem, conditions which promote cap moisture will increase disease severity.

For ginger blotch and pitting, prevention of contamination with ‘P. gingeri’ or ‘P. costantinii’ inoculum is therefore of primary importance:

- cook-out of growing rooms and disinfection of casing and compost handling machinery are essential

- testing of raw materials using the above Taqman PCR tests on enriched samples may identify the source of contamination.

Sterilisation and chemical control

Sterilizing casing materials has given variable results on blotch control and may reduce mushroom yields by adversely affecting beneficial Pseudomonads (P. putida) that stimulate mushroom initials to form.

There are currently no approved chemicals for control of blotch. Watering mushrooms with solutions of calcium chloride, hydrogen peroxide or compost ‘tea’ have been ineffective in controlling blotch.

Developing new control methods

Alternatives to peat casing

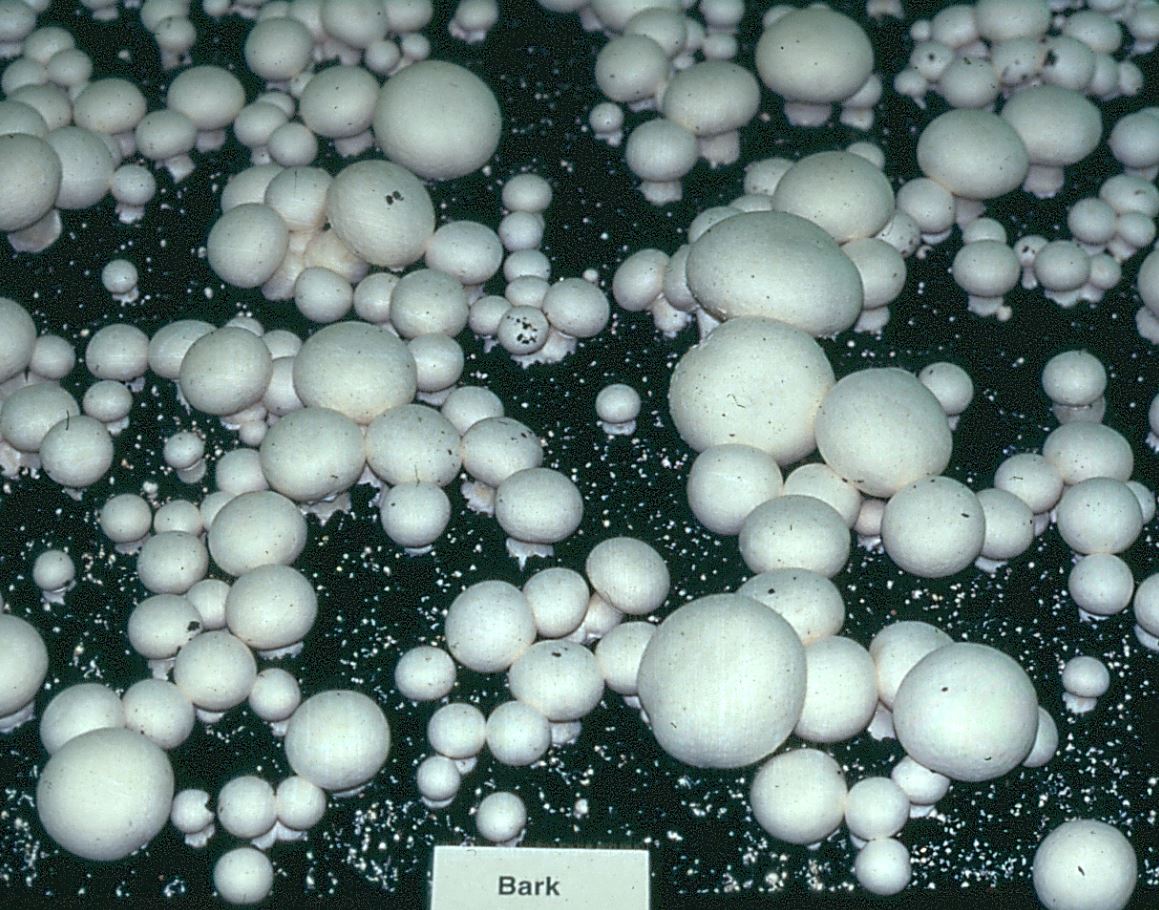

With environmental pressure on the use of peat, there is increasing interest in non-peat casing materials. Research in AHDB Project M 60 and in the Netherlands (Taparia et al. 2021) has shown that incorporation of materials such as bark (Figure 11), fermented grass fibres or recycled cooked-out casing into fresh peat casing can reduce the incidence of blotch, possibly by promoting a casing microbiota which is antagonist to blotch causing pathogens.

Ralph Noble

Ralph Noble

Figure 11: Mushrooms growing on 25% bark casing

Antagonists

Experimental work in AHDB project M 065 has shown that applying Pseudomonad strains that are antagonists to blotch-causing pathogens can reduce the incidence of blotch. This approach requires further development in terms of optimizing the timing and concentration of the antagonist inoculum application to the casing.

Bacteriophages

A range of bacteriophages that can target most of the pathogenic isolates of P. tolaasii, P. costantinii and ‘P. gingeri’ and not affect other non-pathogenic species (potentially beneficial) have been assembled in AHDB project M 065. These phages will have to be further tested in controlled conditions. Future registration of bacteriophages for control of blotch will require some resources.

Useful links

Read about other mushroom diseases

Trichoderma aggressivum in mushrooms

Authors

Dr Joana Vicente (Fera Science Ltd), Dr Ralph Noble (Microbiotech Ltd) and Professor George Salmond (University of Cambridge)

Topics:

Sectors:

Tags: